User-Centred Disco

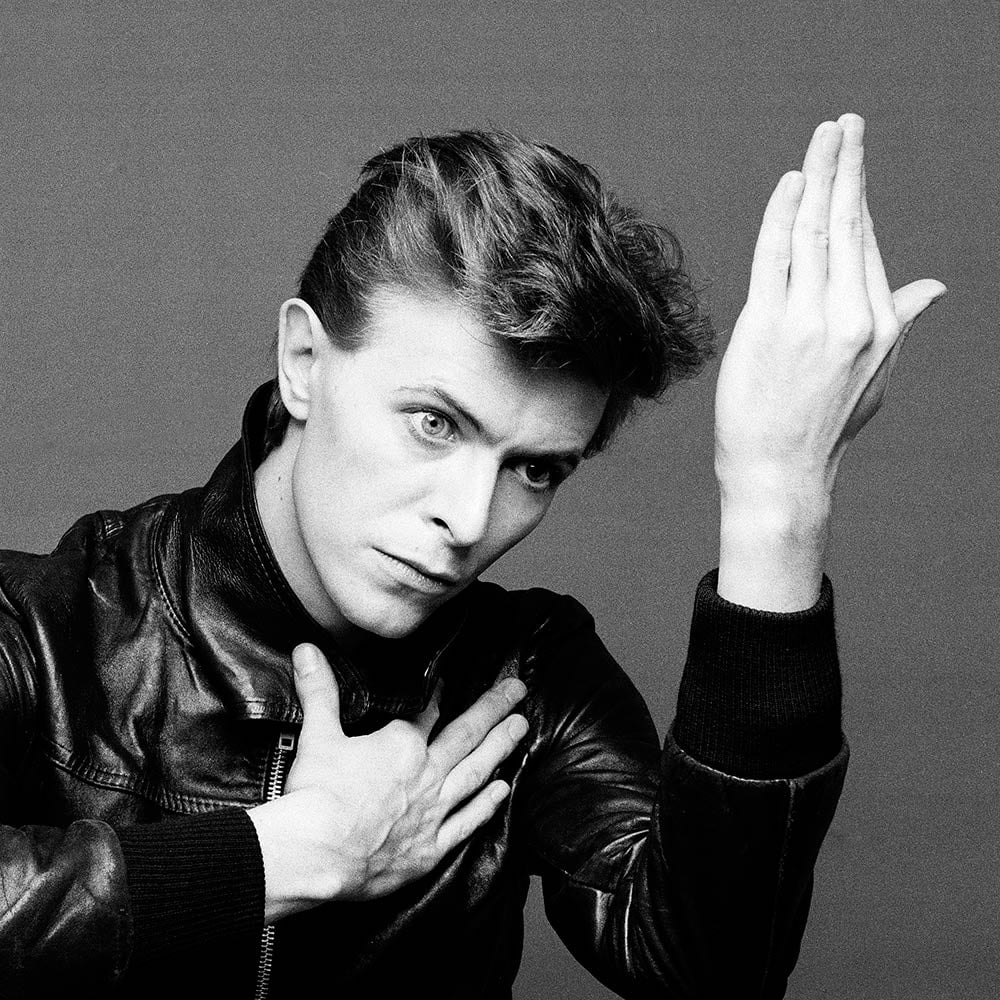

There wasn’t much going on in Belleville, so Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson got into music. Like a lot of high school kids, they played in garage bands, but more importantly, they listened. Every night the airwaves brought the sounds of Charles “The Electrifyin’ Mojo” Johnson from Detroit, playing an eclectic mix of P-Funk, Prince, and… Kraftwerk.

Something about this monotonous, mechanical music struck a chord with these children of car factory workers. “It sounded like somebody making music with hammers and nails”, said May. Where Motown’s music factory embraced the method of Henry Ford’s assembly line, this music captured the feeling of growing up in the industrial decay of Detroit. Listening to Mojo’s show every night made them aware of the power of music to connect and unite people. They were inspired to become DJs themselves, and started to pick up slots on the local party circuit.

Playing records in front of crowds was nothing new in itself. But unlike their contemporaries, May and Atkins weren’t satisfied with merely rocking the party. They wanted to take their audience on a journey.

“We never just took it as entertainment… we used to sit back and philosophise on what these people thought about when they made their music.”, said May. “We built a philosophy behind spinning records. We’d sit and think what the guy who made the record was thinking about, and find a record that would fit with it, so that the people on the dancefloor would comprehend the concept. When I think about the brainpower that went into it! We’d sit up the whole night before the party, think about what we’d play the following night, the people who’d be at the party, the concept of the clientele. It was insane!”

More than just providers of good times, they saw themselves as the bridge between the musicians and the crowd, weaving the records into a narrative that ebbed and flowed, but left the dance floor in a profoundly different state of mind by the end of the set.

Lean Music Creation

Playing other people’s records was all well and good, but Atkins, May and Saunderson felt that to truly express themselves, they needed to produce music of their own.

Traditionally, the process of publishing records was a long and expensive one. Artists might be able to make a first demo on cheap home equipment, but if they wanted to record something they could release, they would need to book time in a recording studio and hire producers, engineers and perhaps session musicians. Next came the process of mixing, mastering and pressing up vinyl. Only then did the song reach the listeners’ ears, and there was every chance our artist had spent a lot of time, money and effort producing something nobody liked.

The Belleville Three took a different approach. They turned to the newly affordable electronic synthesisers favoured by the likes of Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk. With their shared pool of second-hand cast-offs, they were able to skip the expensive studio and record in their own homes, directly onto tape. They could tweak instrument sounds and rearrange their compositions on the fly. And when they thought they had something good, they could simply play it at the Detroit Music Institution on a Saturday night and see how people liked it.

Iterative Techno

“Mayday [Derrick May] was the star of the show,” said DJ and producer Alan Oldham. “Many times, he’d play tracks right off a Fostex two-track recorder that he’d just cut hours before at his studio, something I never got over. He’d beat mix between the reel-to-reel and 1200s [turntables] and back, using the pitch control on the reel. Derrick in those days did by hand what many of the current Techno producers do digitally. No DATs. No acetates.”

The effect of this rapid user testing was twofold. For the artists, they could get invaluable feedback on how effective their new material was before they spent lots of money pressing up vinyl records. But for their fellow musicians in the crowd, this early, open sharing of ideas was both an inspiration and a challenge. Juan Atkins’ “Off To Battle”, recorded under his Model 500 alias, was “a battle cry to keep the standards high.”

Future Shock

With the rise of big data and machine learning, the music of the Belleville Three has a renewed relevance. “This city is in total devastation”, said Derrick May in 1985. “Detroit is passing through its third wave, a social dynamic which nobody outside this city can understand. Factories are closing, people are drifting away, and kids are killing each other for fun. The whole order has broken down. If our music is a soundtrack to all that, I hope it makes people understand what kind of disintegration we’re dealing with.”

This was about more than just making people dance: this was their way of standing up against the destruction of their city, their society, their future. Music as a unifying force, a way to bring people together under a shared experience, and putting the people back in charge of the machines.